Will athletics still be the major Olympic sport by 2020? It’s a good question but unless, as one time member of the European Athletics Association (EAA), Luciano Barra wrote in 2007, we face major challenges with the political will to effectively overcome them, then the answer is almost certainly, no.

Other sports are fast modernising, making themselves commercially viable by attracting investment, ensuring their product is worthy of television coverage and looking to their future by making sure young people find it attractive enough to want to participate. Fatally athletics is doing none of these things.

You don’t have to scratch far below the surface glitz and glamour of the IAAF events to discover a sport in penury, reliant entirely on meagre government handouts and the goodwill and financial generosity of volunteer officials and coaches. Like much else in athletics this is a throwback to a different age but we seem loathe to depart from it. Even at international level anyone visiting any of the 2009 Golden League meetings for the first time in 25 years would not find that much has changed apart from an over preponderance of East African runners in the distance events.

The IAAF and its regional and national federations have failed for years to translate the pulsating excitement of Olympic, World and European championships into its other promotions. They appear as parodies of the real thing. In 2002 the Commonwealth Games came to Manchester; it was a week of exhilaration and success unparalleled in British athletics. In the polls, for the blink of an eyelid, athletics moved ahead of football in popularity. But nothing subsequently changed. British Athletics and its commercial arm were incapable of cashing in on the enthusiasm generated. The stadium switched to football and it seemed symbolic that athletics was demoted to the warm up track.

Two years before Barra wrote his comment the IAAF was told all this, quite forcefully, at a workshop in Monaco. Television representatives pointed out their declining interest in a sport that seemed unwilling to change. Heads were sagely nodded but this year has seen a further drop in viewing figures for a major championship.

At the beginning of this century television audiences in Britain for international athletics ranged between 5 and 7 million but as the decade has progressed that average has dropped, according to the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) to between 2½ and 3 million for Berlin. There is a similar pattern in other major western countries. It’s caused by the failure of international and national athletics bodies to keep the sport alive in the public eye for long periods of time; it’s caused by a failure to think radically.

Although the projected Diamond League has some innovations that will bring encouragement to more events when you look at the meetings involved there is a distinct sense of déjà vu. Ten of the currently projected fourteen meetings are in Europe, meetings that were criticised at the 2005 workshop for their repetitious nature.

A major event in this year’s Golden League was the 5000 metres. Of a total of 91 entries 76 came from East Africa, many taking part in more than one meeting. Only six Europeans were invited for the whole series. Can the promoters not correlate these figures with a lack of media and therefore public interest?

The top stars are sucked clean away by the IAAF and the European promoters into the World Athletics Tour to be rarely seen in their own countries. Blanka Vlasic competed only twice in Croatia; Phillips Idowu three times in Britain; Andreas Thorkilsden three times in Norway and Derval O’Rourke not at all in Ireland. And without television coverage how can a sport sustain interest if its stars are so rarely seen domestically?

There is a domino effect. In Britain the top athletes rarely compete below national championship level, the regional championships and major leagues are bereft of such stars. In terms of sponsorship and public interest the organisers have nothing to sell.

Ernest Hemingway, in his great panegyric to bullfighting and toreros, Death in the Afternoon, wrote: “...that is one test of a true amateur sport, whether it is more enjoyable to player than to spectator (as soon as it becomes enjoyable enough to the spectator for the charging of admission to be profitable the sport contains the germ of professionalism).”

Old Papa was right. The problem we have is that immediately below international level track and field is more enjoyable to players (athletes, coaches, officials and families) than to spectators (the general public). Below that level the general public are rarely seen, indeed are rarely welcome. I can only write of Britain but under the national championships (and sometimes even there) if you asked coaches, administrators, parents and friends to leave the stadium, the stands would be empty. Admission is rarely charged, publicity is conspicuous by its absence and the atmosphere is generally unwelcoming. At such levels athletics is totally uncommercial. It’s become extremely self indulgent.

You may well say that it’s the same with most major sports, that there is no correlation between Sunday morning park soccer and the English Premier League. The difference though, is clear. In soccer there are many layers, many of them professional and semi-professional between your Regents Park Sunday kickabouters and Arsenal; in athletics there is an almost instant brutal dichotomy from the professional 0.1% (rich) to the amateur 99.9% (poor) once form, for one reason or another, deserts you. As an athlete one moment you are feted, the next you are yesterday’s man or woman.

Competition is the raison d’être of all sport, it’s certainly the life blood of athletics. So why is it that it’s so piecemeal? Why is it that nationally and internationally there is no holistic approach? In Britain we have had numerous reports on the future of competition but no metaphorical puff of white smoke has ever emanated from Athletics House; the current hotchpotch of mediocrity serves only to turn people away from athletics, especially the general public.

There’s an old proverb that says there’s none so blind as those who will not hear. As the sport collectively turns a deaf ear to the expert advice that it is given, as it sees Usain Bolt as its sole saviour and as it ignores shrinking participation at its grass roots you know deep down that we are in trouble.

Tuesday 20 October 2009

Sunday 27 September 2009

Concrete Ceilings

It is ironic that in a recent interview Gerry Sutcliffe, the British sports minister, castigated the Football Association for not honouring a pledge to make its council more inclusive with greater representation for ethnic minorities , women and fans. “Rugby and cricket got rid of old farts,” Sutcliffe said, “football’s old school cannot continue.” He should look at UK athletics and then pause for further thought as to the action to be taken with soccer.

British athletics discarded its blazerarti but replaced it with an inexperienced bureaucracy supported by selected compliant volunteers that has led the sport into the worst state of its 129 years of existence and will take years to correct. This is the saga of on-going white, male, middle-aged dominance of the control of athletics in Britain that has existed since the AAA was formed in 1880.

In the 1920’s the AAA brusquely rejected overtures for affiliation by a newly formed women’s association despite the fact that English athletes had swept the board at the first women’s international meeting in Monte Carlo. Peter Lovesey wrote in his history of the AAA: “Whether male chauvinists won the day or the AAA simply took fright at controlling what was regarded in some quarters as at best risqué and at worse dangerous to health the WAAA went its own way.”

After almost seventy years the era of separate associations came to an end with the forming of the British Athletics Federation and inexorably positions of power in BAF were immediately and greedily swept up by the men.

In the eight global championships held this century black athletes have won 57% of UK medals; in the same period our women athletes have won just over 56%. Both these percentages are higher than they are both demographically and in terms of athlete participation, with the black athletes considerably so. But in the administrative corridors of power, where vital decision making takes place, both groups are highly conspicuous by their absence. By appointing an ex-black sprint champion and a woman Paralympic champion as non-executive directors UK Athletics believes it has satisfied any criteria laid down by its paymasters. Not so.

The impact of black athletes, mostly but not exclusively from the Caribbean, on our international success, has visibly grown over the last few decades. Indeed it has to be said that our record would be much the poorer without them. Yet the viewpoint of the black athletics community is rarely heard at any level in the sport.

Fringe organisations like the Association of British Athletics Clubs (ABAC) and the British Milers Club (BMC) follow the same pattern as the main governance in being white male dominated.

The autumn of 1967 in the USA saw the emergence of an angry, black sociology professor from San Jose State, Harry Edwards. His athlete acolytes were sprinter Tommie Smith and 400m runner Lee Evans. Both were to win gold at the forthcoming Mexico City Olympics but both had supported Edwards throughout the autumn of 1967 and spring of the following year, in calls for a black boycott of the Games.

The issue was the rampant racism that was still extant in the USA, a racism that was reflected in the Jim Crowism in sporting structures. Edwards was, as one writer put it, “pushed by anger not to radicalism which is only an argument for change, but towards violence or at least the threat of violence.” He orchestrated demonstrations that turned violent at the famous New York Athletic Club (NYAC) indoor meeting at Madison Square Garden in 1968 because he alleged that the NYAC barred blacks and Jews from membership; he demanded that South Africa should continue to be barred from the Olympics because of its apartheid policies. More interestingly Edwards called for the “desegregation of the United States Olympic Committee administrative and coaching staffs.”

There was no boycott but a podium demonstration in Mexico by Smith and John Carlos that was beamed around the world, a silent iconic moment of such power, intensity and even beauty that it helped to shift significantly (but by no means absolutely)attitudes to racism in the US. On a much lesser scale it set in motion changes that would impact on women and black participation in athletics administration with the dissolution of the white, male dominated Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and its replacement by a solely track and field association.

There was no boycott but a podium demonstration in Mexico by Smith and John Carlos that was beamed around the world, a silent iconic moment of such power, intensity and even beauty that it helped to shift significantly (but by no means absolutely)attitudes to racism in the US. On a much lesser scale it set in motion changes that would impact on women and black participation in athletics administration with the dissolution of the white, male dominated Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and its replacement by a solely track and field association.

In 2008 a black woman, Stephanie Hightower, was elected President of USA Track and Field and is Chair of its Board of Directors. Hightower, a former world class hurdler was, at election, Chair of the USATF Women’s Track and Field Committee. Would that happen in the UK? Of course not.

Contrast the democracy and structure of the world’s strongest athletics nation with what occurs in Britain: Hightower’s equivalent, Ed Warner, is appointed (with the mandatory approval of the government’s sporting quangos), not democratically elected by the sport. He has at best little or no background in track and field. Along with the USATF the IAAF has a women’s committee. No part of British athletics has such a committee. Earlier this century a Valuing Diversity programme was set up by UKA covering women, disability and ethnicity. It withered on the vine.

Black coaches have made a great impact on our sport over the past decade. Many of our great sprinters and jumpers have moved from the competitive arena to coaching with ease and success. Only one, the former European triple jump champion and Australia Chief Coach, Keith Connor, has been considered for a major role. But he was twice turned down; firstly for a regional coach’s job in 1990 and secondly in 2003 for the UK Athletics Director of Performance post when he was (along incidentally with van Commenee) extraordinarily overlooked in favour of a sports psychologist with no coaching background, Dave Collins. Rightly disillusioned he returned to Australia; Collins was sacked after four years.

Those male coaches that have been appointed by UKA are on short term contracts. There is no career path for them. When the curtain falls on 2012 a number of those contracts will be terminated. It must be galling for our coaches to find that they (32 global medals this century, 10 gold) are overlooked in favour of an influx of coaches from Canada (7 global medals this century, no gold).

Women have been unable to make such an impact. The only woman coach to be professionally appointed in Britain was former Olympic discus thrower Meg Ritchie who was appointed National Coach for Scotland in 1999. Her background though was not in the UK but as a professional coach in the USA at the University of Arizona and later at Texas Tech. There are other former women international athletes at Level 4 (one even has a MA in coaching) who are producing Olympians but in terms of international duty and other appointments such as the recent national mentor posts or the England managers they are ignored.

And on those rare occasions when women have reached positions of regional responsibility they are met by alien macho behaviour, posturing, shouting down, condescension, caustic e-mails and, in coaching, poaching by predatory males. So when this subject is mentioned to those who govern us, who look sorrowful, metaphorically wringing their hands, saying it is dreadful and something must be done but you see women just don’t apply, it’s a cop out. The real question is whose responsibility is it to ensure far more equitable representation at the decision making levels of the sport (which the IAAF is doing as far as women are concerned)? It is that of UK Athletics and England and the other national bodies who have the power to bring about change.

In his book Souled Out? How Blacks are Winning and Losing in Sport American journalist Shaun Powell surmised that the percentage of blacks participating in a sport should be roughly reflected in the numbers that coach and manage them. The same of course applies to women. Why? Because those who govern athletics in Britain are only hearing one-third of the story; everything that comes to them comes from a white, male perspective. How many of those working in the respective headquarters in Solihull understand the needs of women athletes and coaches? How many can empathise with black athletes and coaches and their lifestyles? Without such understanding there is no mutual way forward. A century of white, Caucasian thought will be further sustained for decades to the detriment of the major Olympic sport in Britain.

And should a woman or black man be lucky enough to be considered for a position in the sport often a dialogue with the deaf ensues and candidates then find, as Powell points out, that the interviewers “rely on a tired formula: Go with whom you know” (and with the present UK hierarchies, whom you employ).

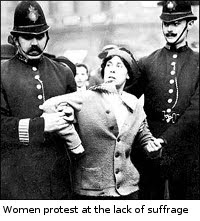

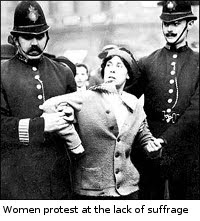

Those who have tried to right these wrongs have soon realised that they have taken on a task of Sisyphus. In order to drill through the concrete ceilings that stop their advancement more cooperation and spirited lobbying is required. Suffrage did not come through women deciding not to ruffle the feathers of men; blacks must remember the courage of Tommie Smith, John Carlos and indeed of the white sprinter Peter Norman who joined their protest on the podium. Each paid a price for his bravery.

Those who have tried to right these wrongs have soon realised that they have taken on a task of Sisyphus. In order to drill through the concrete ceilings that stop their advancement more cooperation and spirited lobbying is required. Suffrage did not come through women deciding not to ruffle the feathers of men; blacks must remember the courage of Tommie Smith, John Carlos and indeed of the white sprinter Peter Norman who joined their protest on the podium. Each paid a price for his bravery.

In the USA there is a Black Coaches Association and a whole raft of women’s coaches associations in many sports. Over a hundred women athletics coaches turned up in Croydon in August for a women’s coaching conference. They could form the power base of a women’s athletics coaching association. Are these the ways forward to bring about a radical change in a century long age of stereotypical thinking? Only time will tell.

British athletics discarded its blazerarti but replaced it with an inexperienced bureaucracy supported by selected compliant volunteers that has led the sport into the worst state of its 129 years of existence and will take years to correct. This is the saga of on-going white, male, middle-aged dominance of the control of athletics in Britain that has existed since the AAA was formed in 1880.

In the 1920’s the AAA brusquely rejected overtures for affiliation by a newly formed women’s association despite the fact that English athletes had swept the board at the first women’s international meeting in Monte Carlo. Peter Lovesey wrote in his history of the AAA: “Whether male chauvinists won the day or the AAA simply took fright at controlling what was regarded in some quarters as at best risqué and at worse dangerous to health the WAAA went its own way.”

After almost seventy years the era of separate associations came to an end with the forming of the British Athletics Federation and inexorably positions of power in BAF were immediately and greedily swept up by the men.

In the eight global championships held this century black athletes have won 57% of UK medals; in the same period our women athletes have won just over 56%. Both these percentages are higher than they are both demographically and in terms of athlete participation, with the black athletes considerably so. But in the administrative corridors of power, where vital decision making takes place, both groups are highly conspicuous by their absence. By appointing an ex-black sprint champion and a woman Paralympic champion as non-executive directors UK Athletics believes it has satisfied any criteria laid down by its paymasters. Not so.

The impact of black athletes, mostly but not exclusively from the Caribbean, on our international success, has visibly grown over the last few decades. Indeed it has to be said that our record would be much the poorer without them. Yet the viewpoint of the black athletics community is rarely heard at any level in the sport.

Fringe organisations like the Association of British Athletics Clubs (ABAC) and the British Milers Club (BMC) follow the same pattern as the main governance in being white male dominated.

The autumn of 1967 in the USA saw the emergence of an angry, black sociology professor from San Jose State, Harry Edwards. His athlete acolytes were sprinter Tommie Smith and 400m runner Lee Evans. Both were to win gold at the forthcoming Mexico City Olympics but both had supported Edwards throughout the autumn of 1967 and spring of the following year, in calls for a black boycott of the Games.

The issue was the rampant racism that was still extant in the USA, a racism that was reflected in the Jim Crowism in sporting structures. Edwards was, as one writer put it, “pushed by anger not to radicalism which is only an argument for change, but towards violence or at least the threat of violence.” He orchestrated demonstrations that turned violent at the famous New York Athletic Club (NYAC) indoor meeting at Madison Square Garden in 1968 because he alleged that the NYAC barred blacks and Jews from membership; he demanded that South Africa should continue to be barred from the Olympics because of its apartheid policies. More interestingly Edwards called for the “desegregation of the United States Olympic Committee administrative and coaching staffs.”

There was no boycott but a podium demonstration in Mexico by Smith and John Carlos that was beamed around the world, a silent iconic moment of such power, intensity and even beauty that it helped to shift significantly (but by no means absolutely)attitudes to racism in the US. On a much lesser scale it set in motion changes that would impact on women and black participation in athletics administration with the dissolution of the white, male dominated Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and its replacement by a solely track and field association.

There was no boycott but a podium demonstration in Mexico by Smith and John Carlos that was beamed around the world, a silent iconic moment of such power, intensity and even beauty that it helped to shift significantly (but by no means absolutely)attitudes to racism in the US. On a much lesser scale it set in motion changes that would impact on women and black participation in athletics administration with the dissolution of the white, male dominated Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and its replacement by a solely track and field association.In 2008 a black woman, Stephanie Hightower, was elected President of USA Track and Field and is Chair of its Board of Directors. Hightower, a former world class hurdler was, at election, Chair of the USATF Women’s Track and Field Committee. Would that happen in the UK? Of course not.

Contrast the democracy and structure of the world’s strongest athletics nation with what occurs in Britain: Hightower’s equivalent, Ed Warner, is appointed (with the mandatory approval of the government’s sporting quangos), not democratically elected by the sport. He has at best little or no background in track and field. Along with the USATF the IAAF has a women’s committee. No part of British athletics has such a committee. Earlier this century a Valuing Diversity programme was set up by UKA covering women, disability and ethnicity. It withered on the vine.

Black coaches have made a great impact on our sport over the past decade. Many of our great sprinters and jumpers have moved from the competitive arena to coaching with ease and success. Only one, the former European triple jump champion and Australia Chief Coach, Keith Connor, has been considered for a major role. But he was twice turned down; firstly for a regional coach’s job in 1990 and secondly in 2003 for the UK Athletics Director of Performance post when he was (along incidentally with van Commenee) extraordinarily overlooked in favour of a sports psychologist with no coaching background, Dave Collins. Rightly disillusioned he returned to Australia; Collins was sacked after four years.

Those male coaches that have been appointed by UKA are on short term contracts. There is no career path for them. When the curtain falls on 2012 a number of those contracts will be terminated. It must be galling for our coaches to find that they (32 global medals this century, 10 gold) are overlooked in favour of an influx of coaches from Canada (7 global medals this century, no gold).

Women have been unable to make such an impact. The only woman coach to be professionally appointed in Britain was former Olympic discus thrower Meg Ritchie who was appointed National Coach for Scotland in 1999. Her background though was not in the UK but as a professional coach in the USA at the University of Arizona and later at Texas Tech. There are other former women international athletes at Level 4 (one even has a MA in coaching) who are producing Olympians but in terms of international duty and other appointments such as the recent national mentor posts or the England managers they are ignored.

And on those rare occasions when women have reached positions of regional responsibility they are met by alien macho behaviour, posturing, shouting down, condescension, caustic e-mails and, in coaching, poaching by predatory males. So when this subject is mentioned to those who govern us, who look sorrowful, metaphorically wringing their hands, saying it is dreadful and something must be done but you see women just don’t apply, it’s a cop out. The real question is whose responsibility is it to ensure far more equitable representation at the decision making levels of the sport (which the IAAF is doing as far as women are concerned)? It is that of UK Athletics and England and the other national bodies who have the power to bring about change.

In his book Souled Out? How Blacks are Winning and Losing in Sport American journalist Shaun Powell surmised that the percentage of blacks participating in a sport should be roughly reflected in the numbers that coach and manage them. The same of course applies to women. Why? Because those who govern athletics in Britain are only hearing one-third of the story; everything that comes to them comes from a white, male perspective. How many of those working in the respective headquarters in Solihull understand the needs of women athletes and coaches? How many can empathise with black athletes and coaches and their lifestyles? Without such understanding there is no mutual way forward. A century of white, Caucasian thought will be further sustained for decades to the detriment of the major Olympic sport in Britain.

And should a woman or black man be lucky enough to be considered for a position in the sport often a dialogue with the deaf ensues and candidates then find, as Powell points out, that the interviewers “rely on a tired formula: Go with whom you know” (and with the present UK hierarchies, whom you employ).

Those who have tried to right these wrongs have soon realised that they have taken on a task of Sisyphus. In order to drill through the concrete ceilings that stop their advancement more cooperation and spirited lobbying is required. Suffrage did not come through women deciding not to ruffle the feathers of men; blacks must remember the courage of Tommie Smith, John Carlos and indeed of the white sprinter Peter Norman who joined their protest on the podium. Each paid a price for his bravery.

Those who have tried to right these wrongs have soon realised that they have taken on a task of Sisyphus. In order to drill through the concrete ceilings that stop their advancement more cooperation and spirited lobbying is required. Suffrage did not come through women deciding not to ruffle the feathers of men; blacks must remember the courage of Tommie Smith, John Carlos and indeed of the white sprinter Peter Norman who joined their protest on the podium. Each paid a price for his bravery.In the USA there is a Black Coaches Association and a whole raft of women’s coaches associations in many sports. Over a hundred women athletics coaches turned up in Croydon in August for a women’s coaching conference. They could form the power base of a women’s athletics coaching association. Are these the ways forward to bring about a radical change in a century long age of stereotypical thinking? Only time will tell.

Friday 11 September 2009

That's All Folks!

As with Bugs Bunny so it is with the ever shortening athletics season. For the general public Athletics 2009 has been about nine, pulsating days in Berlin and Usain Bolt; for aficionados it’s been around nine weeks. But now it’s all over and it’s time to lower the curtains. It is not finis, of course, if you live in the southern hemisphere, where the season is just starting. Not so you’d notice in the northern half of the globe because news from the south is minimal.

When the IAAF launched its new Diamond League in March its President, Lamine Diack said: “It has always been one of our dreams to see the circuit of our best meetings going to each corner of the world. And today, we are all sitting here and are proud to say that the dream has come true.” Well, not quite.

Of the fifteen selected meetings eleven are in Europe, two are in the USA and one each in Asia and the Arabian Peninsula. By not travelling south of the equator great cities like Sydney (2000 Olympics); Melbourne (2006 Commonwealth); Rio de Janeiro (bidding for 2016 Olympics); Auckland (1990 Commonwealth Games); Johannesburg (1998 World Athletics Cup); Cape Town (2010 FIFA World Cup); Jakarta (2011 South-East Asia Games) will not see the world’s very best athletes in action.

How can this be? How is it that other sports like rugby, cricket, golf, tennis, soccer, play at a high level for nine or more months of the year, taking their competitions to southern climes when it is out-of-season in the north (or vice-versa) whilst athletics, apart from some cross-country and indoor, goes into training hibernation after more like nine weeks?

It’s partly habit, of course, the old “well, we’ve always done it this way” beloved of so many in athletics including, regrettably, many coaches. Little research has been carried out on the comparative physiological requirements of different sports but I find it difficult to believe that they are so much greater in track and field than they are in, say, tennis, where the best players, for nine months or so, can play upwards of fifteen hours competitive tennis in a week between flying to venues around the globe. And still train.

Anyway, many athletes run week-in, week-out arduous cross-country races and sprinters and jumpers compete in indoor meetings; athletes of undoubted talent from Australia and New Zealand in particular have always travelled northwards in search of fame and fortune after their summer seasons.

John Landy did it in the fifties as did Herb Elliott, Ron Clarke and Murray Halberg in the following decade. The late Andy Norman persuaded the New Zealanders John Walker, Rod Dixon and Dick Quax to come to Europe every year for the summer season with no detrimental effect on their performances. Most of the above set world records in the northern hemisphere. More recently Craig Mottram ran the Europe circuit for a number of seasons. So it appears that talented southern hemisphere athletes can endure up to eight months of combined competing and training without harmful effects on performance. It surely follows that European and American athletes can do likewise.

To truly reach, with the Diamond League, “each corner of the globe” as Diack put it, the IAAF has to do one of two things. It either has to extend the programme by another six meetings or so or it has to cut down on the number of European meetings on the circuit. Given the close ties between the European promoters and the world governing body this might prove difficult. Some of the proposed meetings have a long history with the Weltklasse at the Leitzegrund track in Zurich, for instance, going back over 80 years.

But if we are to embrace what the IAAF calls “the athletics family” south of the equator, if we are to help develop the sport in that vast area, then tough decision will have to be taken.

The IAAF is to be congratulated on its concept which is certainly more equitable in terms of the distribution of events and of prize money but its success will be governed by the television coverage that it can attract. The whole series needs to be aired ideally on terrestrial television but at least on mainstream satellite and certainly not tucked away on obscure pay-to-view channels in various countries. Without television world-wide the Diamond League will be just another self-indulgent exercise by a sport that needs to frequently convince itself that it is more important than it really is.

A Pretence of Democracy

Steve Backley, one of the world’s all-time great javelin throwers, is the interim vice-president of the UK Members Council a body that meets twice annually to sustain the pretence that democracy reigns in our sport in Britain.

He now has to go through an election process to confirm his original appointment. Knowing Steve as I do then, should there be such an election process (doubtful as you will see), it is more than likely that he would get my vote being perfectly capable of expressing robust views where necessary.

It is the process of this election that should give grave concern to the vast majority of the sport. It is a similar procedure as is operated by England Athletics where recently, some may remember, a challenger to the incumbent chairman was rejected by an Establishment vetting panel appointed to assess candidature suitability.

A similar all-white, all-male athletics establishment junta has been set up to decide whether suggested candidates can become nominations to challenge Steve. Whilst not suggesting that the vetting panel has anything but fairness and the good of the sport at heart it is surely right to point out that the process is open to abuse and manipulation. It is also a process (no doubt instigated by our unelected sporting quangos)that looks so daunting that very few would seemingly wish to undertake it which is probably the whole purpose of the exercise.

What is extraordinary is the submissiveness of the rank and field of British athletics to the processes that have over the past twelve years eroded its ability to influence the development of the sport. Typical of the docility has been the total lack of protest and even comment on the administrative changes made by England leading to the abolition of the nine regional offices and as a consequence the demotion of the nine regional councils to talking shops. The auguries for the replacements are not propitious but all this has been greeted by a deafening silence.

“To stand in silence,” said Abraham Lincoln, “when they should be protesting makes cowards out of men.”

Thursday 3 September 2009

Pawns of Power

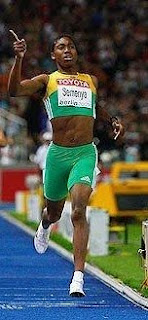

Twice in twenty-one years two young South African women athletes have been caught up in the power politics of world sport. In 1988, Zola Budd a 21 year old white woman from the highveld near Bloemfontein became a pawn in the battle to save the Seoul Olympics from yet another boycott. In 2009 Caster Semenya an 18 year old black woman from Aganang in Limpopo province has been deemed the victim of sexism and racism by no less a man than Jacob Zuma, President of South Africa.

Budd was an extraordinarily talented runner who set records in South Africa that would never be recognised because the country was ostracised from world sport through its apartheid policies. As her grandfather was English the 17 year old was rushed to Britain by her avaricious father Frank, received a passport almost overnight and was thus eligible to compete in the Los Angeles Olympics. Controversy rode her back from that moment.

Whilst in LA she inadvertently tripped-tumbled to the track the American favourite Mary Slaney ensuring that neither of them would win a medal and earning for herself a lasting notoriety. Over the next three years she won two world cross-country championships and set British and Commonwealth records. But most of the time she was homesick, spending more and more time in Bloemfontein finally catching the eye of Sam Ramsamy, the powerful head of SANROC (South African Non Racial Olympic Committee). The frail, diminutive runner, it seemed to him, was a God given gift as the epitome of apartheid.

The 1986 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh had been boycotted because of renegade rugby and other sport’s tours to South Africa. New Zealand was fearful that its 1990 Games in Auckland would suffer the same fate; it was also due to stage the World cross-country championships in 1988 where Budd was due to run. Horse-trading took place between the country and SANROC. The deal was that if the Kiwis kept Budd out of the championships SANROC would ensure there would be no boycott of the Commonwealth Games. The campaign was successful; Budd was harassed on cross-country courses in England; Scandinavian and African countries wrote to the IAAF asking for an investigation. The story was world-wide news; the pressures on Budd were enormous. The British Amateur Athletic Board (BAAB) reluctantly withdrew her from the team as much for her sake as anyone else’s.

The President of the IAAF, Primo Nebiolo had assured the International Olympic Committee (IOC) President, Juan Antonio Samaranch that Budd would not be in Seoul thus preventing yet another boycott. In March, 1988 the IAAF suspended Budd until its next Council meeting, ironically to be held in London, alleging that she had “taken part” in meetings in South Africa.

The IAAF Council and the world’s media descended on the Park Lane Hotel in April. It was a weekend of obduracy on all sides. Press conference followed press conference. The BAAB, to its everlasting credit, refused to condemn Budd until evidence was produced that showed that she had participated in meetings in South Africa. That evidence was never forthcoming. All she had done was follow a road race on a bicycle and then at a track meeting been introduced to the crowd. The IAAF construed this as “taking part”; the BAAB did not.

Sensing blood after the New Zealand affair the big guns of African sport joined in, including Lamine Diack from Senegal, IAAF Council member and President of the African Athletics Confederation (CAA) who led the attack on Budd and the BAAB. This is the same Lamine Diack, now President of the IAAF, whose organisation has been accused of racism in the matter of Semenya.

The IAAF instructed Britain to conveniently ban Budd for twelve months. Failure to do so would lead to the country being banned from the Olympics. The BAAB demurred and decided to hold its own investigation. Zola’s formidable Afrikaner mother Tossie flew in, saw the state of her daughter and sent her back to South Africa. The saga and the investigation were over.

There is no doubt in my mind that if the BAAB inquiry had followed its course the conclusion would have been that Budd did not compete in South Africa and a massive confrontation with the IAAF and IOC would have taken place. Budd’s return to South Africa halted that. This had been power politics at its worst and did the IAAF little credit.

South Africa re-entered the sporting fold with the release of Nelson Mandela and the return of democracy. Budd represented her country at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona.

On the surface there is little similarity between the cases of Budd and Semenya but dig deeper and they soon appear. Declaring just hours before her running in the 800 final in Berlin that gender tests were to be carried out on Semenya was an act of insensitivity for which the IAAF has been roundly condemned. The last thing that SANROC, CAA, IAAF considered in their eagerness to outdo the others in the Budd case was the athlete herself, taken at age 17 from a cloistered environment in Bloemfontein and cast on to the world stage in a matter of weeks. In both instances a duty of care was absent.

The disingenuousness of Athletics South Africa knows no bounds; its president Leonard Chuene comes out of the Semenya affair with little credit. It studiously ignored the extraordinary improvement of over 16 seconds in 13 months by the young woman; it never asked the question ‘why?’ Clearly without forethought Chuene immediately accused one of the world great multi-ethnic organisations and its black president of racism, an accusation that is so crass as to deserve the derision heaped upon it. Nonetheless such nonsense hasn’t stopped prominent politicians like Jacob Zuma and Winnie Mandela getting in on the act. Inexorably it seems both the IAAF and South Africa are backing themselves into corners from which it will be difficult to extricate themselves without losing face.

In 1986 Diack refused to present Zola Budd with the gold medal at the world cross-country championships; 20 years later at an IAAF Golden Gala he invited her to be his special guest, calling her ‘one of the athletics family’. Budd, now living in South Carolina on a two year work visa so that she can run (successfully) in the American Masters Classics road running series, was stunned. I wonder what she, now 43, thinks as she views the Semenya case.

The media frenzy that followed Zola for four years in the eighties is long gone; for Caster, I suspect, it is just beginning. What is clearly needed is not wild speculation and even wilder headlines but compassion for the young woman from Limpopo.

Honouring Arthur

It’s good to know that moves are afoot to celebrate the life of Arthur Wharton, the world’s first black professional footballer, by erecting a statue to him in the town of Darlington where he arrived in the 1880’s from what is now Ghana. As a goalkeeper he played not only for Darlington but for Preston, Rotherham and Sheffield United. Perhaps athletics should follow suit in view of his achievements.

Wharton was also a great sprinter, I guess the Usain Bolt of his time. In the AAA Championships of 1886, running on cinders at the old Stamford Bridge track in London he set a world best time for 100 yards of 10 seconds, the celebrated ‘even time’. It was later ratified by the AAA for record purposes.

Wharton was a great all-rounder (he represented Darlington Cricket Club at the AAA’s) who after his triumph joined the famous Birchfield Harriers based in Birmingham. He won the AAA’s title again at Stourbridge Cricket Club the following year and then became a successful professional ‘pedestrian’. In 1889 Arthur turned full-time professional footballer. His running days were over for, as Peter Matthews drily points out in The Guinness Book of Athletics Facts & Feats (1982) his goalkeeping “presumably giving him little chance to exploit his speed.”

After his sporting career Arthur Wharton worked for 15 years as a colliery haulage hand in Yorkshire. He died in 1930 after ‘a long and painful illness’ (presumably emphysema) and was buried in an unmarked grave in the pit village of Edlington, a forgotten star. In the late 20th century a football fund raised the money for a headstone which has been in place since 1997. If you want more details go to arthurwharton.com.

After his sporting career Arthur Wharton worked for 15 years as a colliery haulage hand in Yorkshire. He died in 1930 after ‘a long and painful illness’ (presumably emphysema) and was buried in an unmarked grave in the pit village of Edlington, a forgotten star. In the late 20th century a football fund raised the money for a headstone which has been in place since 1997. If you want more details go to arthurwharton.com.Who is we?

I frequently go to the UK Athletics website in the vain hope of gleaning information about what is going on in that organisation. For far too many weeks now I’ve been greeted by a large photo of Olympic champion Christine Ohuruogu standing somewhat sheepishly in front of a blackboard, chalk in hand, on which is written 3½ times, We must get kids more active. Presumably she has been given one hundred lines for not doing so. What I really want to know before the photo is thankfully removed is: who is the 'we'?

Monday 24 August 2009

Berlin Reflections - 3

By providing excitement, earth shattering performances and drama the vibrant world championships in Berlin have been an enormous success. It is amazing to think that just twenty years have elapsed since the city was divided by the Wall behind which probably the most evil of the satellite communist regimes operated with an Orwellian intensity.

For these were above all a happy championships in which dourness seemed to have no place. Led by Usain Bolt and aided or hindered, depending on your point of view, by the mascot Berlino, athletes let their hair down even at moments of high tension(Asafa Powell seem to have undergone a personality change within the nine days).

And it is only a blink in historical terms since the last time major athletics was celebrated in this stadium under the gazes of the Nazi hierarchy whose dreams of Aryan supremacy were shattered by the brilliant Jesse Owens. It was a poignant moment when the grandchildren of Owens and the German long jump silver medallist, Luz Long, saw their grandfathers honoured for the courageous friendship in sporting combat that they displayed in 1936. It was an inspirational thought that saw the initials JO on the vests of yet another victorious US team, tiny compensation perhaps for the shameful treatment that he suffered from the hierarchy of the American Athletic Union (AAU). By withdrawing, through tiredness, from the subsequent American tour of Europe, Jesse was banned for life from his sport.

Before we get carried away we, and in particular the IAAF, must understand that these championships have been but a fleeting comet in the sporting universe. For just nine days in three years out of four, athletics impinges on the public’s consciousness. Otherwise it remains in the shadows cast by soccer, rugby, tennis, golf and cricket (in a few countries) et al. The reason has been clear for some time: athletics provides the competitive excitement for just over a week that the rest of sport provides almost year round. The championships are meaningful competition; the World Athletics Tour meetings are not. Apart from the odd tweak here and there the format of the meetings has not changed in thirty years. The stars appear, the spectators cheer; if it’s Friday it must be Zurich. Those meetings that once were on terrestial television are now banished to satellite. In The Guardian the day after the championships concluded seven pages were devoted to cricket and half a page to athletics. The evidence is clear enough but there seems to be a dangerous complacency that has been detectable among the hierarchy since this was discussed at a workshop in Monaco a few years ago.

Enough. We have witnessed greatness this last week and come to realise one thing: that there are no limits to human endeavour. Well done Berlin and Bolt.

It was clear from the first day of the championships, even watching on television, that there was a more positive attitude from British athletes, certainly a lot more can do than can’t manage. The result was six medals, one ahead of target and more importantly twenty top-eight placings giving UK a total of 81 points. Put into context this equals our medal performance at the 2000 Olympics and is our best top-eight global points total since that year. What has happened?

What has happened is that there is someone in charge who knows about performance, who recognizes the pressures of global championships, who understands coaches and coaching, who doesn’t accept lame excuses, who tells it straight. We haven't had that for some time. Charles van Commenee has partially lifted the dark pall that has hung over the UK’s overall performances at global championships in recent years.

Interviews with members of the team have shown that this is a significant change. World bronze medallist Jennifer Meadows described him as ‘hands on’; silver medallist Lisa Dobriskey said that the coach told the team that athletics was “yesterday’s sport”, especially after Beijing. “That hit home,” she said. This is in sharp contrast to the eyewash delivered by the sport’s spin doctors. In recent years there is no doubt that some of our athletes have believed the publicity spun around them to sell tickets for our major meetings.

Add this to the fact that in the various age group championships this summer Britain’s young athletes have accrued a total of thirty-nine medals and you may think that we’re on the yellow brick road to 2012.

Hold it there for a moment. The top echelon of the sport cannot exist in isolation. The base of the pyramid must be strong and in our case it isn’t. The vast majority of the clubs in the UK are dysfunctional; the coaching scheme is in disillusioned disarray; our competition structures, especially at junior level, only serve mediocrity. Unless urgent, radical attention is paid to this general malaise the flow of promising talent will swiftly dry up.

Breaking News

The IAAF today said that it had requested the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA) to test Usain Bolt to ascertain that he was human. This followed rumours and innuendos from fellow athletes and their coaches that the Jamaican was, in fact, an alien being. “These performances are out of this world,” said one sprinter. “The guy aint human,” said another. “I mean he runs faster than I drive,” said the grandmother of another 200 metre finalist.

“We have had to act,” said an IAAF spokesman. “What has clinched it for us are persistent reports from Jamaica that on 21 August 1986 a UFO was spotted hovering over the village of Trelawney. NASA tells us that verification of Bolt’s status may take between 3000 and 5000 years owing to the number of planets from which he could have arrived. We’re prepared to be patient. This is a very sensitive issue especially for the athlete and his family. If it is proved that he is an alien then we’d be happy to submit full verification of his times in Berlin to the relevant association on whatever planet.”

When questioned on this possibility Bolt stared very hard at his interrogator who promptly melted away on the spot. He laughed off suggestions that he was the forerunner of a number of aliens being sent to earth to eradicate present world records in preparation for a takeover of the planet.

Kenenisa Bekele was unavailable for comment.

For these were above all a happy championships in which dourness seemed to have no place. Led by Usain Bolt and aided or hindered, depending on your point of view, by the mascot Berlino, athletes let their hair down even at moments of high tension(Asafa Powell seem to have undergone a personality change within the nine days).

And it is only a blink in historical terms since the last time major athletics was celebrated in this stadium under the gazes of the Nazi hierarchy whose dreams of Aryan supremacy were shattered by the brilliant Jesse Owens. It was a poignant moment when the grandchildren of Owens and the German long jump silver medallist, Luz Long, saw their grandfathers honoured for the courageous friendship in sporting combat that they displayed in 1936. It was an inspirational thought that saw the initials JO on the vests of yet another victorious US team, tiny compensation perhaps for the shameful treatment that he suffered from the hierarchy of the American Athletic Union (AAU). By withdrawing, through tiredness, from the subsequent American tour of Europe, Jesse was banned for life from his sport.

Before we get carried away we, and in particular the IAAF, must understand that these championships have been but a fleeting comet in the sporting universe. For just nine days in three years out of four, athletics impinges on the public’s consciousness. Otherwise it remains in the shadows cast by soccer, rugby, tennis, golf and cricket (in a few countries) et al. The reason has been clear for some time: athletics provides the competitive excitement for just over a week that the rest of sport provides almost year round. The championships are meaningful competition; the World Athletics Tour meetings are not. Apart from the odd tweak here and there the format of the meetings has not changed in thirty years. The stars appear, the spectators cheer; if it’s Friday it must be Zurich. Those meetings that once were on terrestial television are now banished to satellite. In The Guardian the day after the championships concluded seven pages were devoted to cricket and half a page to athletics. The evidence is clear enough but there seems to be a dangerous complacency that has been detectable among the hierarchy since this was discussed at a workshop in Monaco a few years ago.

Enough. We have witnessed greatness this last week and come to realise one thing: that there are no limits to human endeavour. Well done Berlin and Bolt.

It was clear from the first day of the championships, even watching on television, that there was a more positive attitude from British athletes, certainly a lot more can do than can’t manage. The result was six medals, one ahead of target and more importantly twenty top-eight placings giving UK a total of 81 points. Put into context this equals our medal performance at the 2000 Olympics and is our best top-eight global points total since that year. What has happened?

What has happened is that there is someone in charge who knows about performance, who recognizes the pressures of global championships, who understands coaches and coaching, who doesn’t accept lame excuses, who tells it straight. We haven't had that for some time. Charles van Commenee has partially lifted the dark pall that has hung over the UK’s overall performances at global championships in recent years.

Interviews with members of the team have shown that this is a significant change. World bronze medallist Jennifer Meadows described him as ‘hands on’; silver medallist Lisa Dobriskey said that the coach told the team that athletics was “yesterday’s sport”, especially after Beijing. “That hit home,” she said. This is in sharp contrast to the eyewash delivered by the sport’s spin doctors. In recent years there is no doubt that some of our athletes have believed the publicity spun around them to sell tickets for our major meetings.

Add this to the fact that in the various age group championships this summer Britain’s young athletes have accrued a total of thirty-nine medals and you may think that we’re on the yellow brick road to 2012.

Hold it there for a moment. The top echelon of the sport cannot exist in isolation. The base of the pyramid must be strong and in our case it isn’t. The vast majority of the clubs in the UK are dysfunctional; the coaching scheme is in disillusioned disarray; our competition structures, especially at junior level, only serve mediocrity. Unless urgent, radical attention is paid to this general malaise the flow of promising talent will swiftly dry up.

Breaking News

The IAAF today said that it had requested the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA) to test Usain Bolt to ascertain that he was human. This followed rumours and innuendos from fellow athletes and their coaches that the Jamaican was, in fact, an alien being. “These performances are out of this world,” said one sprinter. “The guy aint human,” said another. “I mean he runs faster than I drive,” said the grandmother of another 200 metre finalist.

“We have had to act,” said an IAAF spokesman. “What has clinched it for us are persistent reports from Jamaica that on 21 August 1986 a UFO was spotted hovering over the village of Trelawney. NASA tells us that verification of Bolt’s status may take between 3000 and 5000 years owing to the number of planets from which he could have arrived. We’re prepared to be patient. This is a very sensitive issue especially for the athlete and his family. If it is proved that he is an alien then we’d be happy to submit full verification of his times in Berlin to the relevant association on whatever planet.”

When questioned on this possibility Bolt stared very hard at his interrogator who promptly melted away on the spot. He laughed off suggestions that he was the forerunner of a number of aliens being sent to earth to eradicate present world records in preparation for a takeover of the planet.

Kenenisa Bekele was unavailable for comment.

Friday 21 August 2009

Berlin Reflections - 2

The way that the IAAF has brought its querying of the gender of the women’s new World 800 metre champion, 18 year old Caster Semenya, into the public domain just hours before the final of the race in Berlin either indicates a complete insensitivity to the effect of its pronouncements to the world’s media or that a leak of its negotiations with the South African federation was about to take place.

Either way, in its eagerness to indicate its vigilance against “cheating” in whatever form it might materialise the world governing body has shown that such vigilance takes precedence over what should always be foremost in its actions: a duty of care to the athletes.

Media reaction across the world has been inevitable with lurid headlines and sensationalist news bulletins. The family has not been spared. If the way that the story was handled on BBC News is any indication of world reaction this is something that will not do the sport any favours and will tarnish what has been a great championships. That the IAAF did not foresee such a reaction is extremely worrying.

The organisation is right to investigate the rumours and innuendo that have been circulating since Semenya burst on the world scene a few weeks ago but it should surely afford a vulnerable young athlete and her family the same privacy and protection that it does to those who have failed an A drug test by withholding any information until all procedures, including a B test, have been completed. Rumours are one thing, a factual statement quite another.

The IAAF has yet to tell us why it decided to suddenly produce such a bombshell pronouncement just hours before Semenya was to run in the most important race of her life. Very cynical speculation might suggest that it was in the hope that the athlete would withdraw from the final thus avoiding possible future embarrassment should she win gold.

Platitudes of sympathy towards Semenya from IAAF officials have done nothing to lessen the impact of their statement. This is a story that will run and run to the detriment of the organisation and to the sport.

Gender verification is a complicated process and almost twenty years ago the IAAF recommended that mandatory testing, so degrading to women, should cease. The IOC followed suit at the turn of the century. One is reminded of the story of the Polish sprinter Ewa Klobukowska, a European champion and individual Olympic medallist. In 1967 she was banned from the sport, her records and medals expunged for “having one chromosome too many.”

In the case of young Caster the suspicions of athletes have turned to sympathy as the world media turns its glare on a vulnerable young runner and her remote village in South Africa. Not a day the sport can be proud of.

Not many athletes have fairy tale endings to their careers but on Tuesday night in the magnificent Berlin Olympic stadium, in front of a German crowd highly desirous of the country’s first gold medal, 37 year old javelin thrower Steffi Nerius achieved just that. To me it was reminiscent of the first World Championships back in Helsinki in 1983 when Tiina Lillak, also in the javelin, battled to give Finland its only gold.

There was a significant difference. In Helsinki it was a foreign athlete, the British thrower Fatima Whitbread, who put the crowd through agonies with a first round throw that was to lead for six rounds till Lillak’s final effort; in Berlin it was Nerius who took the lead with her first endeavour and then, with the increasingly anxious crowd, had to sit out six rounds whilst the world’s best throwers, including the world record holder Barbora Spotáková, attempted to overtake her. Nerius had just one other serious throw, 65.81m, which would not have gained her a medal of any hue.

It was meant to be just a fond farewell to one of Germany’s greatest throwers; after all she was not top ranked in her country in 2009. That honour, along with the accompanying pressure to win, fell to Christina Obergföll (who finally finished fifth). Apart from winning the European title in 2006 Steffi had always, as the saying goes, been the bridesmaid in global championships. Who was to say that, in the avowed very last international competition of her career, it would be any different?

This time the Gods that decree these things smiled on Steffi, in the same way that they smiled on Tiina twenty-six years ago. The Finnish crowd roared her last throw to the gold medal and the champion then embarked on, as I remember it, a lap of honour that would have seriously challenged the Finnish 400 metre record. Steffi, as becomes a veteran, just soaked up the adulation of the crowd.

She says that she is determined not to change her mind about retiring and you can see her point. How do you follow winning your only global title just three years before your fortieth birthday in front of your home crowd in a stadium filled with so many ghosts? In the 1936 Olympics Ottilie Fischer won the javelin for Germany. Perhaps it was she who had lobbied the Gods.

The condescending put down of Jessica Ennis’s coach, Tony Minichiello, by UK Athletics Chairman, Ed Warner, is a classic example of the crass man management that has plagued the sport for decades.

After the coach had, in a press interview, indicated that he felt Ennis’s preparations had been hindered by UKA’s actions in “decimating” her support team Warner said that he felt that Minichiello had spoken thus because he “was feeling some of the pressure himself just ahead of the competition.” Complete nonsense. What the chairman did not do was answer the points that Minichiello had made: that he had lost a nutritionist, a physiologist and a performance analyst. “They [UKA]” Minichiello said, “changed the way they deliver services and some people had foreshortened contracts. There was no guarantee of jobs.” The above trio voted (as so many others in the sport are doing) with their feet.

All Warner talked about on BBC Radio 5 was future systems, beloved by his organisation and by UK Sport. Evolve a system, tick the box and all will be well. What UKA since its inception has constantly failed to grasp is that systems depend on experienced people for their success. The present highly successful season hasn’t been produced by any system but by individual coaches working, day in and day out, with talented athletes.

It's good to see that someone has sense at UKA. Minichiello, it is reported, has been offered the job of taking charge of milti-events.

Either way, in its eagerness to indicate its vigilance against “cheating” in whatever form it might materialise the world governing body has shown that such vigilance takes precedence over what should always be foremost in its actions: a duty of care to the athletes.

Media reaction across the world has been inevitable with lurid headlines and sensationalist news bulletins. The family has not been spared. If the way that the story was handled on BBC News is any indication of world reaction this is something that will not do the sport any favours and will tarnish what has been a great championships. That the IAAF did not foresee such a reaction is extremely worrying.

The organisation is right to investigate the rumours and innuendo that have been circulating since Semenya burst on the world scene a few weeks ago but it should surely afford a vulnerable young athlete and her family the same privacy and protection that it does to those who have failed an A drug test by withholding any information until all procedures, including a B test, have been completed. Rumours are one thing, a factual statement quite another.

The IAAF has yet to tell us why it decided to suddenly produce such a bombshell pronouncement just hours before Semenya was to run in the most important race of her life. Very cynical speculation might suggest that it was in the hope that the athlete would withdraw from the final thus avoiding possible future embarrassment should she win gold.

Platitudes of sympathy towards Semenya from IAAF officials have done nothing to lessen the impact of their statement. This is a story that will run and run to the detriment of the organisation and to the sport.

Gender verification is a complicated process and almost twenty years ago the IAAF recommended that mandatory testing, so degrading to women, should cease. The IOC followed suit at the turn of the century. One is reminded of the story of the Polish sprinter Ewa Klobukowska, a European champion and individual Olympic medallist. In 1967 she was banned from the sport, her records and medals expunged for “having one chromosome too many.”

In the case of young Caster the suspicions of athletes have turned to sympathy as the world media turns its glare on a vulnerable young runner and her remote village in South Africa. Not a day the sport can be proud of.

Not many athletes have fairy tale endings to their careers but on Tuesday night in the magnificent Berlin Olympic stadium, in front of a German crowd highly desirous of the country’s first gold medal, 37 year old javelin thrower Steffi Nerius achieved just that. To me it was reminiscent of the first World Championships back in Helsinki in 1983 when Tiina Lillak, also in the javelin, battled to give Finland its only gold.

There was a significant difference. In Helsinki it was a foreign athlete, the British thrower Fatima Whitbread, who put the crowd through agonies with a first round throw that was to lead for six rounds till Lillak’s final effort; in Berlin it was Nerius who took the lead with her first endeavour and then, with the increasingly anxious crowd, had to sit out six rounds whilst the world’s best throwers, including the world record holder Barbora Spotáková, attempted to overtake her. Nerius had just one other serious throw, 65.81m, which would not have gained her a medal of any hue.

It was meant to be just a fond farewell to one of Germany’s greatest throwers; after all she was not top ranked in her country in 2009. That honour, along with the accompanying pressure to win, fell to Christina Obergföll (who finally finished fifth). Apart from winning the European title in 2006 Steffi had always, as the saying goes, been the bridesmaid in global championships. Who was to say that, in the avowed very last international competition of her career, it would be any different?

This time the Gods that decree these things smiled on Steffi, in the same way that they smiled on Tiina twenty-six years ago. The Finnish crowd roared her last throw to the gold medal and the champion then embarked on, as I remember it, a lap of honour that would have seriously challenged the Finnish 400 metre record. Steffi, as becomes a veteran, just soaked up the adulation of the crowd.

She says that she is determined not to change her mind about retiring and you can see her point. How do you follow winning your only global title just three years before your fortieth birthday in front of your home crowd in a stadium filled with so many ghosts? In the 1936 Olympics Ottilie Fischer won the javelin for Germany. Perhaps it was she who had lobbied the Gods.

The condescending put down of Jessica Ennis’s coach, Tony Minichiello, by UK Athletics Chairman, Ed Warner, is a classic example of the crass man management that has plagued the sport for decades.

After the coach had, in a press interview, indicated that he felt Ennis’s preparations had been hindered by UKA’s actions in “decimating” her support team Warner said that he felt that Minichiello had spoken thus because he “was feeling some of the pressure himself just ahead of the competition.” Complete nonsense. What the chairman did not do was answer the points that Minichiello had made: that he had lost a nutritionist, a physiologist and a performance analyst. “They [UKA]” Minichiello said, “changed the way they deliver services and some people had foreshortened contracts. There was no guarantee of jobs.” The above trio voted (as so many others in the sport are doing) with their feet.

All Warner talked about on BBC Radio 5 was future systems, beloved by his organisation and by UK Sport. Evolve a system, tick the box and all will be well. What UKA since its inception has constantly failed to grasp is that systems depend on experienced people for their success. The present highly successful season hasn’t been produced by any system but by individual coaches working, day in and day out, with talented athletes.

It's good to see that someone has sense at UKA. Minichiello, it is reported, has been offered the job of taking charge of milti-events.

Monday 17 August 2009

Berlin Reflections - 1

Thanks to modern technology (which I don’t pretend to understand) I was able to watch Jennifer Ennis’s regal progress on the first day of her golden Heptathlon and then on my laptop, courtesy the New York Road Runners website, Paula Radcliffe looking equally majestic winning the New York City Half Marathon.

Whether this run will persuade her to run the marathon in Berlin remains to be seen but the manner of her winning over a classy field that included the leader of the US road running circuit Mamitu Dasku of Ethiopia, her old rival Catherine Ndereba of Kenya and Olympic marathon bronze medallist Deena Kastor (USA) would indicate that she is, to put it at its mildest, in very good shape.

The marathon world record holder broke away after eight miles and in hot and humid conditions pulled away from a pack that never chased her, finishing almost a minute and a half ahead of Dasku and two minutes ahead of Ndereba.

Paula said that she knew her approach to test her fitness was “unorthodox”; Britain’s chief coach Charles van Commenee called it “extreme”. But whichever way you look at it in the end the gal done good.

*

In a song from the musical South Pacific the female lead is described as having every inch of her “packed with dynamite”. The same could be said for the new world Heptathlon champion Jennifer Ennis, only 5’4” (1.62 metres) tall but, in Berlin, high jumped 1.92 metres (and has cleared 1.95m) which indicates quite an extraordinary power-to-weight ratio. If the IAAF website is still correct Ennis has overtaken the Greek high jumper Niko Bakoyanni by one centimetre in clearing a bar 33 centimetres over her own head.

The event was all over almost after the opening discipline and though the shot put has been billed as a hiccup her winning margin of 238 points is the biggest since Carolina Kluft’s Olympic win in 2004. Compared with Kluft’s European record Ennis’s performances in Berlin exceeded the Swede in three of the eight events.

Van Commenee, after a turgid few weeks in which he feared picking up the phone in case it was to herald another withdrawal through injury, can now smile. The UK has more than a world champion it has someone who can spearhead the sport towards 2012.

*

Leaving aside Usain Bolt’s breaktaking new world 100 metres record the interesting man to me in that epic race was the bronze medallist Asafa Powell. Heavily criticised for “bottling” at previous attempts at global championships, panicking when challenged and tightening up, Powell looked a totally different man at the start emulating his fellow countryman with dubious antics to the camera.

Whether all sprinters will now emulate Bolt’s actions before races remains to be seen but they clearly do not suit Powell’s style but what I think has really helped him is Usain Bolt. By running that extraordinary world record in Beijing Bolt clearly showed his fellow Jamaican a superiority that for him, at least, is insurmountable. He’s lost the world record; the pressure is off so there was no ‘tying up’ in his bronze medal run in the German capital.

As for Dwain Chambers he showed a maturity and humbleness throughout that the European promoters would now do well to match. If he had breathed in at the finish he could have well gone under 10 seconds.

*

Remember the ballyhoo when it was announced some months ago that the great and the good of British endurance running past were to help Ian Stewart rise to the challenge of reviving this particular ailing section of our sport? As it turns out it was pure PR-speak.

When questioned on BBC television Brendan Foster and Steve Cram both admitted that the group that also includes Paula Radcliffe, Seb Coe and David Bedford, “hadn’t met yet.” Moreover Steve said that they hadn’t really got any brief. Clearly this is one of those ideas that seemed good at the time.

Leaving aside the question as to why endurance running should be singled out for special treatment when so many other events in British athletics are in equally bad shape one has to comment that all this was and is part of the puff that continually emanates from UK Athletics. The rose tinted spectacles with which they view the sport are certainly not curing their myopia.

Whether this run will persuade her to run the marathon in Berlin remains to be seen but the manner of her winning over a classy field that included the leader of the US road running circuit Mamitu Dasku of Ethiopia, her old rival Catherine Ndereba of Kenya and Olympic marathon bronze medallist Deena Kastor (USA) would indicate that she is, to put it at its mildest, in very good shape.

The marathon world record holder broke away after eight miles and in hot and humid conditions pulled away from a pack that never chased her, finishing almost a minute and a half ahead of Dasku and two minutes ahead of Ndereba.

Paula said that she knew her approach to test her fitness was “unorthodox”; Britain’s chief coach Charles van Commenee called it “extreme”. But whichever way you look at it in the end the gal done good.

*

In a song from the musical South Pacific the female lead is described as having every inch of her “packed with dynamite”. The same could be said for the new world Heptathlon champion Jennifer Ennis, only 5’4” (1.62 metres) tall but, in Berlin, high jumped 1.92 metres (and has cleared 1.95m) which indicates quite an extraordinary power-to-weight ratio. If the IAAF website is still correct Ennis has overtaken the Greek high jumper Niko Bakoyanni by one centimetre in clearing a bar 33 centimetres over her own head.

The event was all over almost after the opening discipline and though the shot put has been billed as a hiccup her winning margin of 238 points is the biggest since Carolina Kluft’s Olympic win in 2004. Compared with Kluft’s European record Ennis’s performances in Berlin exceeded the Swede in three of the eight events.

Van Commenee, after a turgid few weeks in which he feared picking up the phone in case it was to herald another withdrawal through injury, can now smile. The UK has more than a world champion it has someone who can spearhead the sport towards 2012.

*

Leaving aside Usain Bolt’s breaktaking new world 100 metres record the interesting man to me in that epic race was the bronze medallist Asafa Powell. Heavily criticised for “bottling” at previous attempts at global championships, panicking when challenged and tightening up, Powell looked a totally different man at the start emulating his fellow countryman with dubious antics to the camera.

Whether all sprinters will now emulate Bolt’s actions before races remains to be seen but they clearly do not suit Powell’s style but what I think has really helped him is Usain Bolt. By running that extraordinary world record in Beijing Bolt clearly showed his fellow Jamaican a superiority that for him, at least, is insurmountable. He’s lost the world record; the pressure is off so there was no ‘tying up’ in his bronze medal run in the German capital.

As for Dwain Chambers he showed a maturity and humbleness throughout that the European promoters would now do well to match. If he had breathed in at the finish he could have well gone under 10 seconds.

*

Remember the ballyhoo when it was announced some months ago that the great and the good of British endurance running past were to help Ian Stewart rise to the challenge of reviving this particular ailing section of our sport? As it turns out it was pure PR-speak.

When questioned on BBC television Brendan Foster and Steve Cram both admitted that the group that also includes Paula Radcliffe, Seb Coe and David Bedford, “hadn’t met yet.” Moreover Steve said that they hadn’t really got any brief. Clearly this is one of those ideas that seemed good at the time.

Leaving aside the question as to why endurance running should be singled out for special treatment when so many other events in British athletics are in equally bad shape one has to comment that all this was and is part of the puff that continually emanates from UK Athletics. The rose tinted spectacles with which they view the sport are certainly not curing their myopia.

Wednesday 12 August 2009

When the Blind lead the Blind

The blindness of those currently running the governing bodies of British athletics to the current disillusionment, frustration and inevitable anger of voluntary administrators, coaches and officials is matched only by that of the quangos who govern them. It means that the promised great new dawns for the sport frequently handed down from on high have remained ephemeral. Ten years of disenfranchisement have taken a severe toll. The enthusiasm and innovative entrepreneurship of volunteers that were once a hallmark of British athletics have been sucked dry by a bureaucracy that doesn’t perceive that athletics has a soul let alone understand the nature of it.

Whether UK and England athletics will be ready to deal with the enthusiastic aftermath of the London Olympics is already questionable just under three years before 2012.

The recent cynical emasculation of the voluntary regional councils by those who run England Athletics displays the contempt with which they view experienced volunteers. Funding has been cut off making the councils more impotent than they were before. In the very north of England (and it may very well be the same elsewhere) important competitions and other programmes for the benefit of athletes have had to be cancelled through a lack of funding.

There has been no explanation of why, just a few years after they were heralded as the right way forward for the sport the professional offices of the nine regions were abruptly shut down creating an unsavoury game of musical chairs for jobs in a hastily concocted new hierarchy. But what’s new? Those that run British and English athletics are so comfortably entrenched that they see no need whatsoever to account for their actions to the rank and file of the sport.