“You,” said the late Andy Norman, in that often mimicked, slightly rasping, fruity voice to the tall, majestic black man, who had just asked a favour, “you couldn’t fill a telephone box.” The recipient of this remark was the man who would become Britain’s greatest ever sprinter, Linford Christie and it delighted him to quite frequently remind Andy of his absolutely false prognosis.

“Bums on seats” though was an imperative of Norman and he mostly succeeded at various televised meetings around the country throughout the eighties. The most difficult to sell was the AAA’s with its interminable heats structure and a look at the 2007 meeting (now sadly renamed the UK Championships) at Manchester’s Sports City showed that things haven’t changed much.

It has recently been announced that the Olympic Trials and UK Championships will move to the piecemeal Alexander Stadium in Birmingham and memories have been stirred of some great championships there in the past. 1988 was a particularly vintage year: a baking hot weekend, large crowds, a star-studded cast and intense drama – all the ingredients that have made British athletics great in the past.

But it doesn’t matter where the venue is, if the structure isn’t right then the crowds won’t come. Indeed, if they become bored and restless they’ll not return and the numbers will swiftly fall away as they have done in Manchester. With nostalgia now dispensed with for expediency’s sake, it is the right time to look at the format of this 128 year old meeting.

The biggest mistake, in my judgement, has been to try and entice the public in over all three days by spreading a number of finals. What should be done is to run during the whole of Friday and Saturday an entire programme of track heats and semi-finals with field event pools/finals. Sunday can be then be a star studded affair displaying, within a 3 hour or so programme, the very best of our athletes competing in finals and for places in a major championships. Small adjustments could be made to the programme (perhaps semi-finals and finals for 100 metres on the Sunday) but that should be the general format. Such a programme would simulate, to a certain extent, a major championship with every track event except the longer distances having heats and semi-finals. It would encourage a greater entry.

The aficionados – coaches, relatives, officials – will attend on the first two days anyway but on the third day the publicity should be concentrated on attracting the general public, of selling the sport and filling the stadium. Even at this level of competition the emphasis is still insular: of pleasing ourselves, of doing everything as we’ve always done it and frankly of being somewhat smug about it. We have ignored the Hemingway dictum that as soon as a sport becomes enjoyable enough to the spectator for the charging of admission to be profitable, it becomes entertainment.

That great panjandrum of Performance, Dave Collins, should be persuaded that places at the Olympics et al are not solely his and his team’s patronage but are prizes to be won in combat. Athletes and coaches need to know well in advance exactly what they have to do to make teams; they should not to have to wait for the puff of smoke to emanate from Athletics House, accompanied by some tedious, clichéd homily. The paying public too deserve to know that if athletes achieve a qualifying standard and finish first or second in an event they will be going to Beijing or Berlin or Barcelona. It’s no good calling a trial a Trial if it appears to have no bearing on selection. In the past this cut throat part of the championships was a major selling point for the public.

And what about the two track walks that take up an inordinate amount of time in the programme? They have been there, in one form or another, since 1880 and when you saw such great world class exponents and Olympic medallists as Stan Vickers, Ken Matthews and Paul Nihill strut their stuff, they were tolerable. But their milieu was the open road over 20 and 50 kilometres and sitting for almost an hour watching even these men walking twenty-five laps around a track tested the patience and even the soul of spectators many of whom would decide it was the moment for a cuppa.

Today these events are pure tedium; the great days of great British competitive walking having long gone. Last year at 20 kilometres our top walker Dan King ranked sixth in the world; our second ranked walker, Andy Penn, came 73rd. This sounds great until you realise that I am talking about the women’s ranking lists. Penn was, at 20K, only a fraction under 2 minutes faster than our top woman, Jo Jackson. It seems to me that the various governing bodies should either get behind walking in a big way or put it out of its misery. It is a disgrace that these events are still on the programme and the 10,000 metres, once a great highlight, is relegated to some far flung outpost of the sport. If we must have walks then make them road walks with finishes in the stadium.

The argument against running the 10,000 metres in the main championships is that by omitting it you enable runners to compete at both 5 and 10K (not something that any current British runner would contemplate at World or European level). But British athletes, like Gordon Pirie and David Bedford, have achieved the double in the past, when the championships were run over just two days. The neglect of the 10,000 metres Europe wide is appalling and to paraphrase one of our greatest ever coaches, where there are no 10K races there are no 10K runners. Only ten British runners beat 30 minutes (and Paula’s record) last season. This event badly needs a showcase and it should be restored to the championship weekend.

None of this is rocket science. But, as with competition generally, there is a great lethargy about the national championships. Our sport has been in a deep slumber and woken to find it’s no longer as great as we thought it was. Hey guys (regretfully few gals) its 1670 days, as I write, and counting.

Don’t Mention Christine

Could we now have moratorium on Christine Ohuruogu? Can we all – athletes, coaches and administrators – adopt a Trappist vow on her drug case? It has raised more hackles and more debate than if she had actually failed a drug test. The problems have lain, not with the athlete but with those who have a visceral belief that anybody failing to abide by the rules is a drug cheat and should be banned for life. In Christine’s case (and with many others who are now admitting to missing tests) it is, as well as her own carelessness, the sheer inflexibility of the system that is also at fault.

It does not seemed to have dawned on those at UK Sport who administer anti-doping that if an athlete is into imbibing performance enhancing drugs he or she and whoever is monitoring their intake is going to be damned careful that they do not get caught evading tests. It is, to say the least, self-defeating as Konstadinos Kederis and Ekaterina Thanou found out in 2004. So the Independent Sampling Officers (ISOs) catch the careless and the great hullabaloo that has accompanied Christine over the past eighteen months ensues. More flexible arrangements of these matters would not ensure that those into steroids would get away with it.

The problem is that so many in our sport believe that there should be a lifetime ban for those guilty of a doping offence (not necessarily of doping). However when it comes down to the legalities and a little word called justice wiser heads prevail over emotions and over the decades the maximum sentences for doping have fluctuated between two and four years, with a lifetime ban for a second offence.

Many over-zealous administrators and sections of the media are, however, very unhappy with this situation and are constantly looking for ways and means to circumvent it. The British Olympic Association’s (BOA) pernicious bylaw that hands down a lifetime Olympic ban for doping is a classic example and, it appears, is also a means of subverting accepted sporting law.

Both the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and World Anti Doping Agency (WADA) rules do not go nearly as far and the former president of the latter, Dick Pound, went so far as to recently criticise the BOA (globally almost on its own with such a rule) for its sanctimonious insistence of continuing with it. He went so far as to suggest that if tested in a court of law the bylaw may well be found to be unlawful as well as unjust.

But arguments about all of this are for another day. I understand from a spokesperson for UK Athletics that Christine will shortly begin to receive the benefits she deserves from World Class Podium and will be travelling to South Africa next month on the excellent UKA preparation camp in South Africa. Good news at last for this most beleaguered of athletes.

Sunday 16 December 2007

Wednesday 5 December 2007

The Cautionary Tale of William Snook

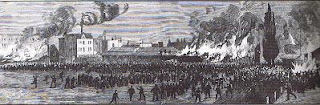

Snook was the sacrificial lamb in a harsh campaign conducted by the fledgling Amateur Athletic Association against what it considered to be the scourge of the sport, professionalism. Their thinking was haunted by a challenge match between two professional runners staged at London’s Lillie Bridge track during that same year. Thirty thousand people turned up to see the two fastest men of the day, Harry Gent and Harry Hutchens, battle it out over 100 yards. Bookmakers thronged the arena, but neither athlete started because each of their rival gangs wanted to arrange for their man to lose, and so the crowd set the stadium ablaze in their anger.

The major problem that the AAA faced was betting. Pedestrianism, where cheating was rife, had dominated the decades leading up to the AAA’s formation in 1880 and it continued to blight amateur athletics. Athletes were persuaded to lose races they could have won; professionals posed as amateurs; amateurs posed as other amateurs especially in the popular handicap races of the time. It was disorganised chaos and the AAA determined that if it was to have any credibility as an organisation it would have to severely implement the second of its Objects of Association: “to deal repressively with any abuse of athletic sports.” It also seemed determined that its repressions of order would not be sidetracked by any miscarriage of justice.

It was a cold, bleak day in March 1886 with a hint of snow in the air when the runners gathered in Croydon for the National Cross-Country Championships. Snook, the defending champion, was odds on favourite to win by the numerous bookies that were present. Originally he had been a team mate of the great W.G. George at Moseley Harriers where their celebrated rivalry was intense. Walter, however, had moved over to the professional ranks to challenge its best miler William Cummings and Snook now ruled the roost. In 1885 he won four AAA titles in the championships at Southport, three on a Saturday and one, the 10 miles, in a record time on the Monday.

Snook did not win in Croydon though. He was overtaken in the closing stages of the race by J E Hickman of Godiva Harriers and finished second. A month later came a sensational announcement: Snook was disqualified for life from the amateur ranks by the Southern Committee of the AAA for “roping”. What had prompted this extraordinary move by the governing body to banish its leading runner?

Snook’s major problem was that this was not his first offence. In 1881 he was suspended for a year by the Northern AA for conniving at the entry of a professional at an amateur meeting at Southport. Snook continued to compete at meetings not affiliated to the AAA. The AAA then threatened any athletes who competed with Snook with suspension. The organisation would remember him when he again appeared before them five years later.

A month after his 1886 suspension Snook appealed. It was clear that, in contravention of English law, he would have to prove his innocence rather than the AAA prove his guilt. He said he was below his usual weight on the day and had suffered from sore feet in the closing stages. The AAA, already suspicious, did not believe him. Rumours had been rife that Snook had deliberately thrown the race to aid the bookies, presumably for some remuneration. His appeal was thrown out by 15 votes to 11. A second appeal, backed by the Midlands AAA, was lost by 13 votes to 12. Finally the matter was raised at the next AGM when, after a long discussion that went well into the night, a motion for reinstatement was lost by 26 votes to 16. Snook was finished as an amateur. The evidence against him had been subjective and circumstantial, but he could not disprove it. He provided the AAA with a major scapegoat to warn other amateur runners of the day.

The AAA continued on its draconian path. In 1882 it had financed the Northern AA to enable it to prosecute for fraud a professional posing as an amateur. He was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment with hard labour. Over the next twenty years there were many similar cases and imprisonment for six months with hard labour was not an uncommon punishment

Payments to athletes was the AAA’s second biggest problem after betting. Many top stars were paid by clubs to appear at their meetings to boost attendance. In order to catch miscreants it adopted the principle of Queens Evidence: indemnifying those willing to provide evidence. This meant that club secretaries who had offered payment to athletes often sat in judgment on them for accepting them. In 1896 six top British athletes were accused of receiving appearance money and five were banned for life. Others followed and by the end of 1897 the leading British runners for each event from 100 yards to 20 miles were disqualified from competing sine die. The next great distance runner Alfred Shrubb became so fed up with the AAA deciding where and when he could run abroad that he defied them by deciding to race in Canada in 1905. He was suspended for life in 1906 after an investigation into his expenses for the trip. Like all the others he turned professional.

Finally, in 1906, the AAA persuaded the government to introduce a clause into the Street Betting Act that would give power to sports promoters to control betting at their meetings, including calling in the police to deal with objectors. After a quarter of a century the battle was over.

Well, not quite. In the ensuing eighty years many fine athletes, including Paavo Nurmi, the Flying Finn and the Swedes, Arne Andersson and Gunder Hägg, fell foul of the amateur ethos and were suspended. The last great one was Wes Santee, the American miler who was banned in 1955 for abuses of expenses. By 1980, a century after the formation of the AAA, it was obvious that payments to athletes in the celebrated brown envelopes were rife. Two years later the IAAF passed an historic law that enabled athletes to receive payment for competing.

And what of William Snook? He dabbled at professional athletics for a while and then became the licensee of two pubs in Birmingham. Finally he settled in France where he continued running and won a celebrated challenge match in the Bois de Boulogne in 1891. Then he went off the radar until April, 1916 when word reached Birchfield that he was destitute and in bad health in Paris. Athletic supporters raised the funds for hospital fees and to bring him back to England but his health did not improve. He returned to Birmingham in October and was placed in the workhouse at Highcroft Hall where he died two weeks or so before Christmas. He was just 55. He was buried in Wilton Cemetery with few mourners. It was a sad end to a great runner and probably the greatest victim of the AAA’s repressive measures against professionalism.

Bibliography

The Official Centenary History of the AAA by Peter Lovesey, published by Guinness 1979

The History of Birchfield Harriers 1877-1988 by Professor W.O. Alexander and Wilfred Morgan published by Birchfield Harriers 1988 .

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)